WAVELENGTHS

THOUGHTS ON CREATIVITY FROM A LOCALIZATION PERSPECTIVE

In the following series of articles Alpha Creative’s team explore all things creative

from the history of the term, to how collateral needs to be creatively adapted for independent and interdependent cultures to reach success. We also look at how brands can personalize their offerings for each new locale, and talk to the team to find out about their creative inspirations.

Ultimately, AI will speed up production and generate more creative options, allowing the copywriter and creative designer more time to edit the AI output and intentionally introduce error if they’re too bland or too perfect to be credible. As most of our snap decisions are emotionally led, the illogical and the imperfect will always have a significant role to play.

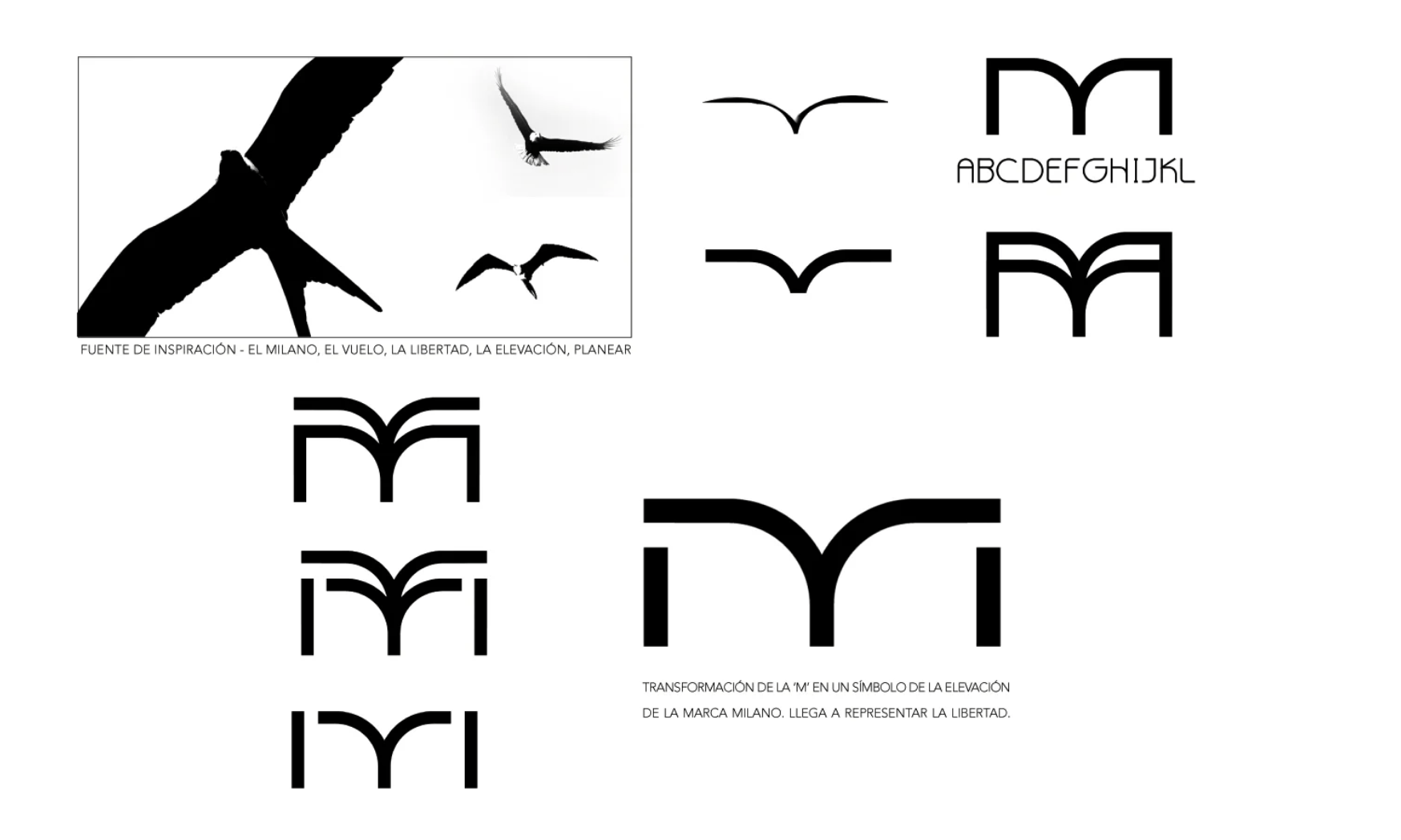

Elevation > bird's wings > letter M > logo design

Creativity and the creative industries are now at a significant crossroads. Generative AI is now being used to create unique and engaging content. We can even alter our prompts and adjust an AI model’s parameters to include well–known copywriting techniques such as the AIDA Framework (which stands for Attention, Interest, Desire, and Action).

Looking forward, AI in the creative process will become a playground where creatives can login to their sandbox, increase and decrease randomness and tweak parameters by coding in strange creative bunches like:

Logical thinking

What comes next is some common sense. Aware that this new logo would need to be read on a clothes label, as well as a store front, I ruled out the use of any intricate or detailed logo design. Similarly, using a plain ‘M’ wouldn’t do the trick, as it gave no sense of elevation. The ‘M’ would need wings.

The zeitgeist

Around that time, camouflage and stencilled fonts were becoming a recognizable trend in fashion. This was the inspiration behind the stencilled effect on the ‘M’, which now gave the impression it was being elevated from its stems.

The whole creative process from start to a finished logo took one afternoon. At the presentation to the client’s marketing manager, both options were laid out on the table. We were half expecting the usual non-committal poker face, but he jumped up from his chair and said, “that’s it!” pointing to option B. There were no changes and no feedback. It went straight to production.

The error of personal experience

Meanwhile, I was still struggling with the name. Unaware that Milano was the Spanish word for Milan, I kept thinking of birds. I had already stumbled on one distraction that would set my thinking apart radically. As a passionate ornithologist, I was just beginning to learn the name of birds in Spanish. Milano was the Spanish name for a bird of prey called the kite.

Strange connections

It may seem strange to get caught up with thinking about birds but there was a clear connection to the brief. One part caught my immediate attention - “We want to elevate the brand...”.

After Googling Milano, I had already noticed that the photo of the red kite I’d seen had angular wings, which, in a peculiar way, resembled the stems of the letter ‘M’. Remember those drawings of birds flying we would create as kids - a squiggle or an ‘M’ at best?

Milan > fashion hub > history > class > heraldry > shield/emblem > icon/logo

The agency director, also a qualified graphic designer, asked me to put together an alternative proposal to the one he was already planning on creating. In one sense this was a lateral vs. lineal thinking approach happening in real time.

From the director’s point of view, I was tasked with creating option B - the ‘ballast’ option. These gently nudge the client towards the agency’s favourite. He was inspired by the company name, Milano (the Spanish name for Milan). Before he began work, I could already see he was adopting a lineal approach:

I’ve been asked many times to explain my profession over the years, often in a conversation that goes as follows:

Them: So, what do you do?

Me: I’m a creative director.

Them (perplexed): Ok, so what do you do then?

Most people don’t get it. Creative direction is a nebulous area where common sense and logic won’t guarantee winning over hearts and triggering action.

Most creative media solutions address the very common problem of audience engagement, specifically the lack thereof. Ultimately, humans are like photons: following the path of least resistance. Because we live in a world with increasingly short attention spans, we shut down our receptors at the first sight of any friction that will encroach on our valuable time.

Watch the scrolling speed of any adolescent on a smart phone. It’s fast. So, what exactly does it take to make that adolescent stop and click? How is creativity and design leveraged to persuade and seduce? How the hell does a creative director come up with an idea that’ll work?

They’re tricky questions as there are many variables. Perhaps the only certainty is that some of the most provocative creative thinking often originates from lateral thinking, not vertical or lineal thinking.

One of the most insightful ways to understand lateral thinking is to see the process at work. Unfortunately, many vital parts of this thinking are hidden in the recesses of the mind. Whether conscious or subconscious, we see the results of creative thinking, but are rarely informed of the inspiration and thinking behind it.

To get this complete perspective on creative lateral thinking, we need to get personal. Let’s imagine we’re programming an algorithm, and we need to pick apart how a creative mind responded to a real brief and delivered a successful solution. We now know that generative AI, with the correct prompts and the correct control of randomness, can achieve some outstanding visual and text-based output, with minimal need for human input. We can now replicate those ‘rabbit -in-the-hat’ creative moments by controlling randomness, and by adding degrees of error combined with critical thinking and imaginative interpretations of the results. Generative AI will help creative directors to expedite the creation of options, but it will still require the input of personal experience to create the uniqueness we so often see in successful creative campaigns.

Let’s jump to Spain in the mid-nineties, to a modest communications agency where I worked as creative director. A new brief came in from the agency director: one of Spain’s male fashion retailers required a rebrand. They wanted to become more relevant to the younger generation and be the first choice for fashion conscious males who were contemplating buying their first suit.

01 EDITORIAL

David Standley, Head of Content and Creative

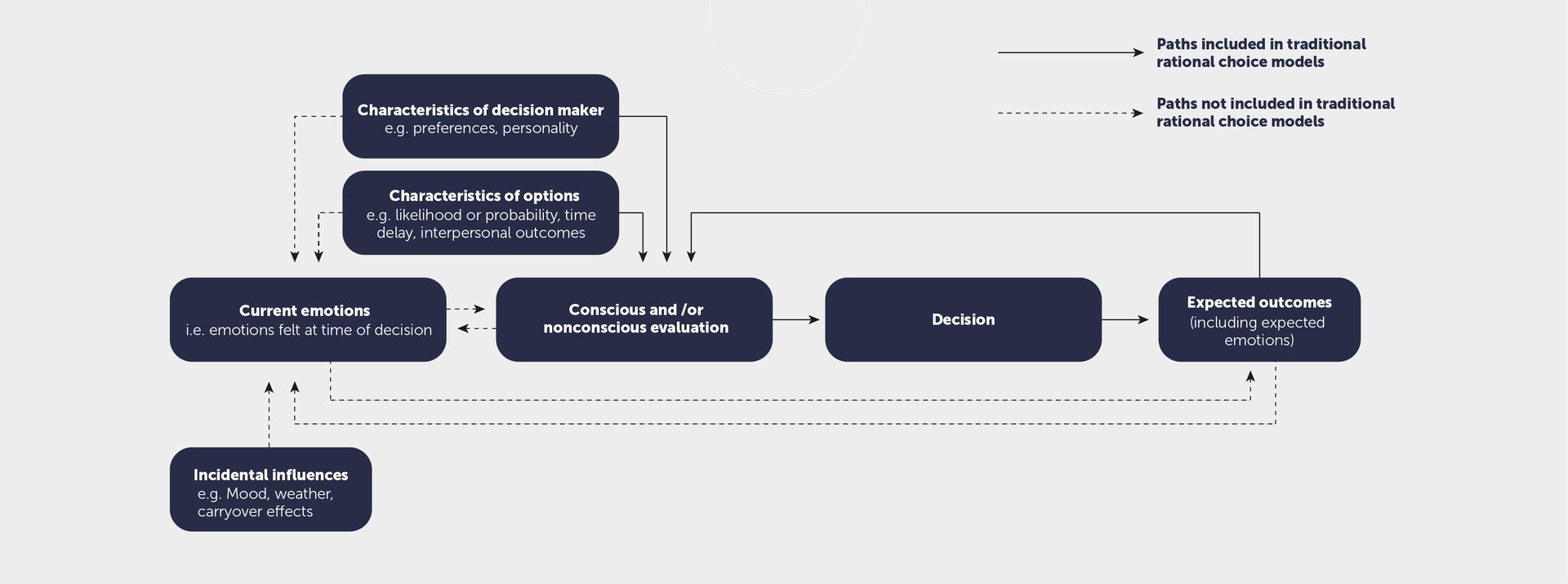

The EIC model shows how various different types of emotion can have profound impacts on the decision-making process, but it’s important to note that branded content cannot directly control some of the stages involved. Instead, when planning content, brands should focus on the ‘characteristics of options’ and the ‘expected outcomes’ areas of the EIC model, which are perhaps best modified through the use of tone. Incidental influences such as the weather are, in spite of how hard we might wish otherwise, beyond the brand’s control.

Research from Robert Heath, David Brandt and Agnes Nairn, published in the Journal of Advertising Research, draws parallels between an interpersonal communication axiom introduced by Paul Watzlawick, famed Austrian-American psychologist, and the relationships between a brand and its audience. One of five interpersonal communication axioms to be developed by Watzlawick, it distinguishes between “communication”, which is the factual, indisputable content of a message, and “metacommunication”, the emotionally charged qualifier which shapes a message’s tone. For brand content, this “metacommunication” is often known as “creativity”, and it is this emotional creativity, argue Heath, Brandt and Nairn, that builds brand relationships (Heath, Brand and Nairn, 2006).

One need look no further than some of history’s most popular advertisements to see proof of that theory in action. Cast your mind back to the sight of a purple wall as the opening notes of Phil Collin’s In The Air Tonight begin to play in the background. The camera pans and reveals a gorilla sat behind a set of drums, taking in the music. Then, as the chorus hits, the animal launches into a now-iconic drum solo. The Cadbury advert, part of the brand’s ‘a glass and a half full of joy’ series, has little to do with chocolate and provides no explicitly informative content, but is now intrinsically linked with the brand for many UK residents who were hooked the first time they they saw it. It was so successful in fact, that the advertisement was cited as one of the driving factors behind Cadbury’s 6 percent year-on-year revenue growth in Britain, Ireland and emerging markets in 2007.

“Memorable advertisements with higher ‘emotive power’ had a large impact on brand favourability, while the “cognitive power” rating had little effect in either market”

Using this model, it’s possible to identify several areas wherein emotion has had an effect on the rational thought process previously believed to power human decision making. The group’s findings, supported by numerous other items of research into emotional impact, identified that emotion can effect the ways in which audiences perceive certain content features, distort statistics, or set different goals. The group goes further, adding that “current emotions can also indirectly influence decision making by changing predicted utility for possible decision outcomes” (Lerner et al, 2015).

For companies planning content campaigns, the message is clear: while information is important, the emotional state of the audience will determine how they assess that information, and what they remember from it. But what kinds of emotions should content aim to trigger in order to drive engagement?

According to Lerner, Li, Valdesolo and Kassam, so-called “high-certainty emotions” such as happiness, anger and disgust will increase heuristic processing by placing focus on the credibility of the content source instead of the quality of its argument and content (Lerner et al, 2015). This could mean that an audience would be more receptive to the concepts being proposed, and less likely to doubt the information presented.

The importance of emotional connection in creating brand relationships

In their synthesis and analysis of over 35 years of research into the effects of emotion on human decision making processes, published in the Annual Review of Psychology 2015, Jennifer S. Lerner, Ye Li, Piercarlo Valdesolo and Karim S. Kassam identified that “many psychological scientists now assume that emotions are, for better or worse, the dominant driver of most meaningful decisions in life” (Lerner et al, 2015). The group specified several ways in which emotions can impact the decision-making process, and proposed the emotion-imbued choice model (EIC) as shown in the image below.

It’s time to talk about feelings:

The impact of cultural differences in emotion on brand relationships

Heart versus mind in the content landscape

We live in a new age of digital brand engagement and increased globalization, with international audiences sharing information across borders more easily than ever before. Accordingly, it wouldn’t take much for companies to assume that campaigns which resonate with the target demographic in one region can be quickly rolled out to other locales with similar success. However, this assumption unfortunately fails to understand the nuanced role that emotional engagement plays in the process of convincing consumers and employees to engage with a brand, and how that emotional engagement is affected by cultural and linguistic differences.

To create successful content campaigns, all stakeholders involved in their planning, whether consumer or employee focused, need to understand the roles of emotional connection and rationalization in converting the audience into brand users and, ultimately, brand advocates. For content to be globally successful, production teams also need to understand how to adapt their content for international audiences, taking into account local culture and consumer expectations.

Traditionally, branded content, and advertising in particular, is designed to be as informative as possible, helping the audience to make logical, rationalized decisions about whether or not to purchase a product or become invested in a brand. While this approach can produce one-time purchases, it doesn’t typically foster the kinds of long-term brand-consumer or brand-employee relationships that result in brand loyalty and advocacy.

Rather than strictly informative content, it is emotional messaging that generally engages the audience and provides the foundations for brand relationships. These relationships typically begin with a decision on the part of the audience: whether or not to make a purchase or engage with branded content. According to recent psychological research, this is a decision that is heavily influenced by the audience’s emotional state (Lerner et al, 2015).

02 EMOTIONS AND CULTURAL DIFFERENCES

JACK SIMPSON

Indeed, Heath, Brandt and Nairn performed research on subjects in two markets (the US and the UK) to find out the effect that certain advertisements had on brand favourability. The advertisements were assessed with the Cognitive Emotive Power Test (CEP Test), which measures a campaign’s “emotive power” (relating to emotional content) and “cognitive power” (relating to rational content designed to inform) and then shown to an audience which confirmed whether they remembered the advertisement or not. The audience was then asked to rate each company on how positively they regarded it. The experiment showed that memorable advertisements with higher “emotive power” had a large impact on brand favourability, while the “cognitive power” rating had little effect in either market (Heath, Brandt and Nairn, 2006).

Interestingly, Heath, Brandt and Nairn identify research from Robert Bornstein, published in the Psychological Bulletin, which states that when non consciously processed emotional content is processed consciously, its effectiveness is weakened. This is to say that when the audience is able to identify the cause of its emotional state, it is able to rationalize it and dilute the effect. For content campaigns such as advertisement, Bornstein argues that “the less aware consumers are of emotional elements in advertising, the better they are likely to work, because the viewer has less opportunity to rationally evaluate, contradict, and weaken the advertising’s potency”. For companies preparing large, multinational campaigns, whether aimed at consumers or employees, this is of particular note. Any frictions arising due to issues such as cultural dissonance could result in one of two outcomes – an emotional aversion to something that doesn’t reflect the audience’s cultural identity, or a rationalization of the attempt at emotional messaging, and a weakening of the desired effect. Of course, neither option will lead to brand advocacy, which is why it’s important to consider the ways in which strategies for emotional engagement will need to adapt to different regions and target markets.

How emotional interpretation differs between cultures and languages

An increased focus on the emotional salience of branded content brings its own challenges for companies looking to engage their domestic audiences, which are then further complicated by attempts to appeal to globally dispersed communities. While it’s always been known that global collateral has to be altered to ensure that language and figures are correct for each market, this relatively newfound need to connect on a subconscious, emotional level raises questions as to how human emotions may vary across borders, and how big an influence culture has on our thought processes.

In research for Emotion Review, Michael Boiger and Batja Mesquita from the University of Leuven state that “most of our emotions occur in the contexts of social interactions and relationships” (Boiger and Mesquita, 2012). It stands to reason then, that as culture and social norms change, so too should the individual’s emotional response to external stimuli and their understanding of the emotional valence of a given situation.

A 2008 study called Putting the face in context: Cultural differences in the perception of emotions from facial behavior, published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, compared Western and Japanese understandings of a target person’s emotional state. The findings showed distinct differences in how the two groups understood the same situations. Whereas Western audiences focused only on the target person’s facial expressions to discern their emotional state, Japanese audiences took the expressions of other people surrounding the target into consideration as well. The target person wasn’t considered to be as happy when the people surrounding them looked angry or sad (Masuda et al, 2008).

This is potentially due to differences in cultural constructions of the ‘self’. In Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion and Motivation, Hazel Rose Markus and Shinobu Kitayama distinguish between cultures which have an independent view of the self, and those that have an interdependent view of the self. Individuals belonging to cultures with an independent view of the self typically have “faith in the inherent separateness of distinct persons”, and are aware of a typical cultural goal to “become independent from others and to discover and express one’s unique attributes”. In contrast, cultures with an interdependent view of the self believe that the individual “cannot be properly characterized as a bounded whole, for it changes structure with the nature of the particular social context” (Markus and Kityama, 1991).

Individuals from these two distinct cultural backgrounds will, according to Markus and Kitayama, exhibit key differences in how they view their roles in society, and how they build their own self-esteem. In their study, Markus and Kitayama state that people with an independent view of the self will see a need to be unique, express themselves, realize internal attributes, promote own goals and be direct in order to fulfil their role in society. Their ability to express themselves and the validation they receive for their internal attributes would be the foundations of their self-esteem.

Contrast this with people from a society with an interdependent view of the self, who will typically believe that their role in society is to fit in, stay in their proper place, engage in appropriate action for each situation, promote others’ goals and be indirect (Markus and Kitayama, 1991). Here, the ability to adjust, restrain oneself and preserve social harmony are the foundations of self-esteem.

As self-esteem and self-realization are often considered to be at the core of motivational processes, this core difference between how members of independent and interdependent cultures see themselves and their roles in society could have significant impacts on how international companies plan emotionally engaging content. In their research, Markus and Kitayama hypothesize that, while people from independent cultures might be driven by a need to achieve, self-actualize and avoid cognitive conflict, those from interdependent groups might be more motivated to fully realize their own connectedness and interdependence (Markus and Kitayama, 1991).

Content targeting Western audiences then, which typically trends towards the independent cultural model, might see more success if it highlights the ways in which it can help the audience to assert their individuality, and ‘break free’ from the standardized rules of society, separating themselves from the masses. Conversely, content aimed at more interdependent audiences, in markets such as Japan for instance, should promote the brand’s ability to help the audience fulfil their social roles, whether it be through the fulfilment of work or familial responsibilities.

Indeed, Markus and Kitayama identify that, in interdependent cultures, ‘positive feelings about the self should derive from fulfilling the tasks associated with being interdependent with relevant others: occupying one’s proper place and maintaining harmony’ (Markus and Kitayama, 1991). It stands to reason that without the correct motivation, audiences are not going to engage with branded collateral, and are unlikely to form long-lasting brand relationships. . As audiences from different cultural backgrounds are motivated by different stimuli, brand collateral and content will need to vary tone, messaging and emotional valence in order to provoke the ideal response, while remaining consistent with the overarching brand identity.

In order to create strong emotional connections between brand collateral and the audience, the emotional narrative needs to be frictionless and aligned with cultural expectations, as previously identified by Bornstein. By tuning into the daily emotions that consumers and employees face, brands are able to cultivate a feeling of familiarity, one that helps close the gap between the company and its audience. As Boiger and Mesquita found, however, the most prevalent emotions seem to depend on the cultural background of each locale and whether it supports an independent or interdependent view of society. The pair identify studies showing that in Japan, ‘socially engaging emotions’, for instance shame or friendly feelings towards others, were felt more intensely than in American contexts, where ‘socially disengaging emotions’, such as pride and anger, were more prevalent. In short, the social background of a locale defines the emotions, interactions and relationships that the audience engages in (Boiger and Mesquita, 2012).

Somewhat bizarrely, the UK wasn’t the only European market infatuated with a campaign prominently featuring a gorilla in 2007. An animatronic gorilla also starred in Italian drink brand Crodino’s iconic advertisements in a series of somewhat comical situations, each time ordering a Crodino at a bar. The takeaway here is unfortunately not quite as simple as “gorilla equals successful content”, but it’s clear that these advertisements, beloved by audiences in their respective countries, managed to forge an emotional connection that has endured in the teen years since they were introduced.

A new model for understanding interactions with branded content

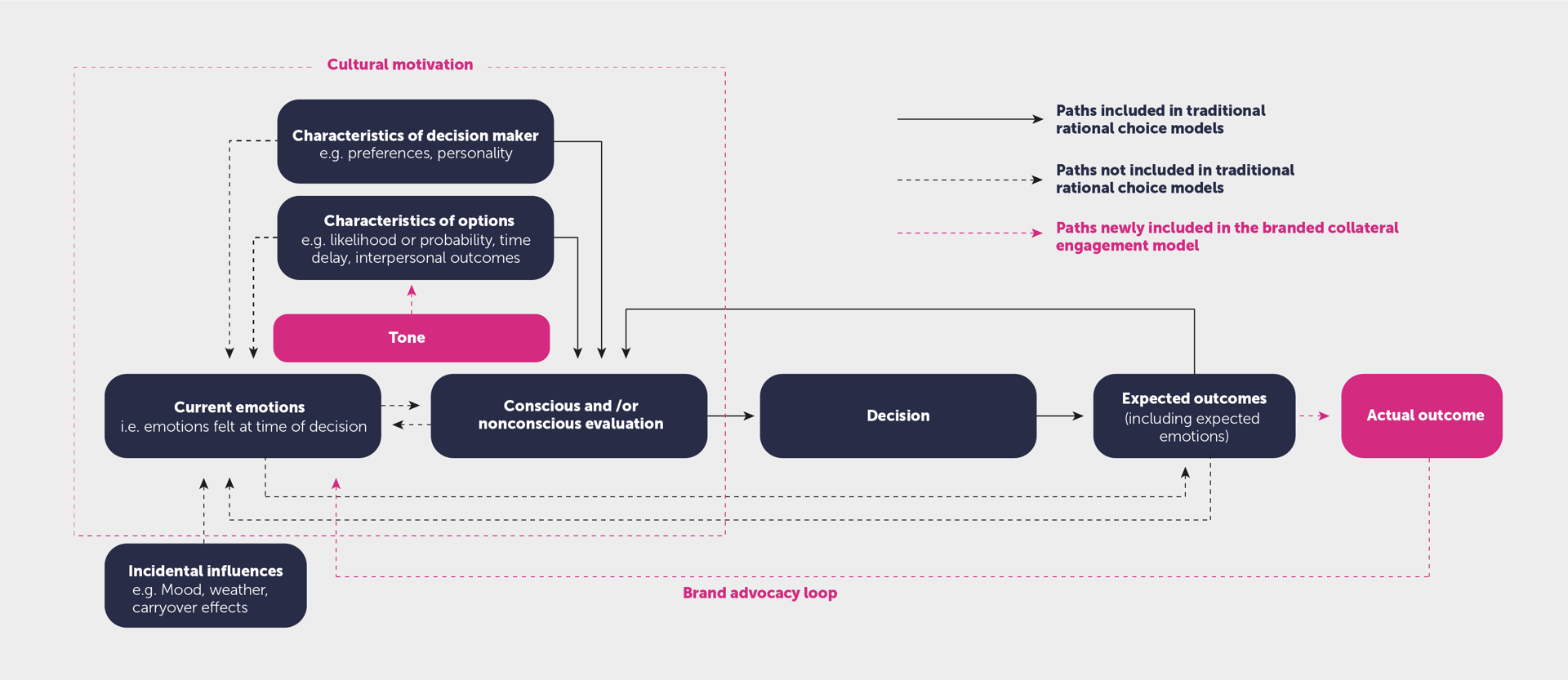

In response to these findings, and to help companies understand the impacts of culture and emotion on audience engagement with branded collateral, this report proposes a modified version of the EIC model, titled the Branded Collateral Engagement model (BCE).

It is believed that by careful understanding of cultural motivation and subsequent development of tone and emotional messaging, brands can develop deeper knowledge of typical ‘characteristics of the decision maker’ and ultimately influence the audience’s perception of the ‘characteristics of options’.

In order to create brand advocates, companies need to leverage their creativity and produce culturally relevant, emotionally resonant narratives that appeal to the audience’s social background and motivate them to engage with the content. By exploring localized social constructs of the self, brands will be able to identify the stimuli that motivate audiences to engage, whether it be through the promotion of individuality and differentiation from the crowd, or through role fulfilment and the strengthening of social harmony. Playing to emotions more prevalent in local society should also help increase the feeling of familiarity between the content and the audience, removing friction from the consumer or employee experience and allowing for more direct engagement with the material.

Indeed, in the Journal of Market-Focused Management, Geok Lau suggests that a consumer will typically ‘examine a brand and judge if it is “similar” to himself or herself. If a brand’s physical attributes or personality are judged to be similar to the consumer’s self-image, the consumer is likely to trust it’ (Lau and Lee, 1999). Here then, expert local insights are needed to ensure that content is created from the ground up in each target market and can resonate with local audiences. Research from George Zinkhan and Jae Hong in Advances in Consumer Research provides further support for this statement, saying that ‘consumers buy or prefer those products which possess images most similar to the images they either perceive or wish of themselves’ (Hong and Zinkhan, 1995).

Lau argues that trust in a brand is also impacted by its predictability, stating that ‘a brand’s predictability enhances confidence because the consumer knows that nothing unexpected may happen when it’s used’ (Lau and Lee, 1999). Building on this idea, the ‘actual outcome’ step has been included in the BCE model.

Whether it’s an employee interacting with training materials or a consumer purchasing a product, if the actual outcome is in line with the emotional ‘expected outcome’, it is likely that the customer will begin to develop feelings of trust towards the brand. Here, it is important that collateral remains tonally consistent and doesn’t overpromise in order to ensure the ‘actual outcome’ and ‘expected outcome’ are in alignment. Through repeated interactions wherein the ‘actual outcome’ and ‘expected outcome’ do not significantly differ, we can hypothesize that the audience should develop brand loyalty, making them more receptive to future branded collateral. In the BCE model, this has been identified as the ‘brand advocacy loop’.

While the current model of creating branded collateral in one language, and then adapting it for other locales can work, the BCE model, alongside findings from Lau, Zinkhan and Hong, indicates that companies would see stronger brand advocacy by concurrently creating content specifically targeted at each region.

Incorporating localization at the start of the content creation pipeline allows teams to design content with an understanding of local ‘cultural motivation’, which will shape the ways the audiences receive content messaging. Teams can then look at using ‘tone’ with greater cultural specificity, meaning they will be able to guide audiences towards positive interpretations of the ‘characteristics of options’ more reliably than before. This will result in branded collateral that is more likely to create favourable feelings towards the brand among the audience, and promote brand advocacy at a fundamental level, creating strong brand image and reputation.

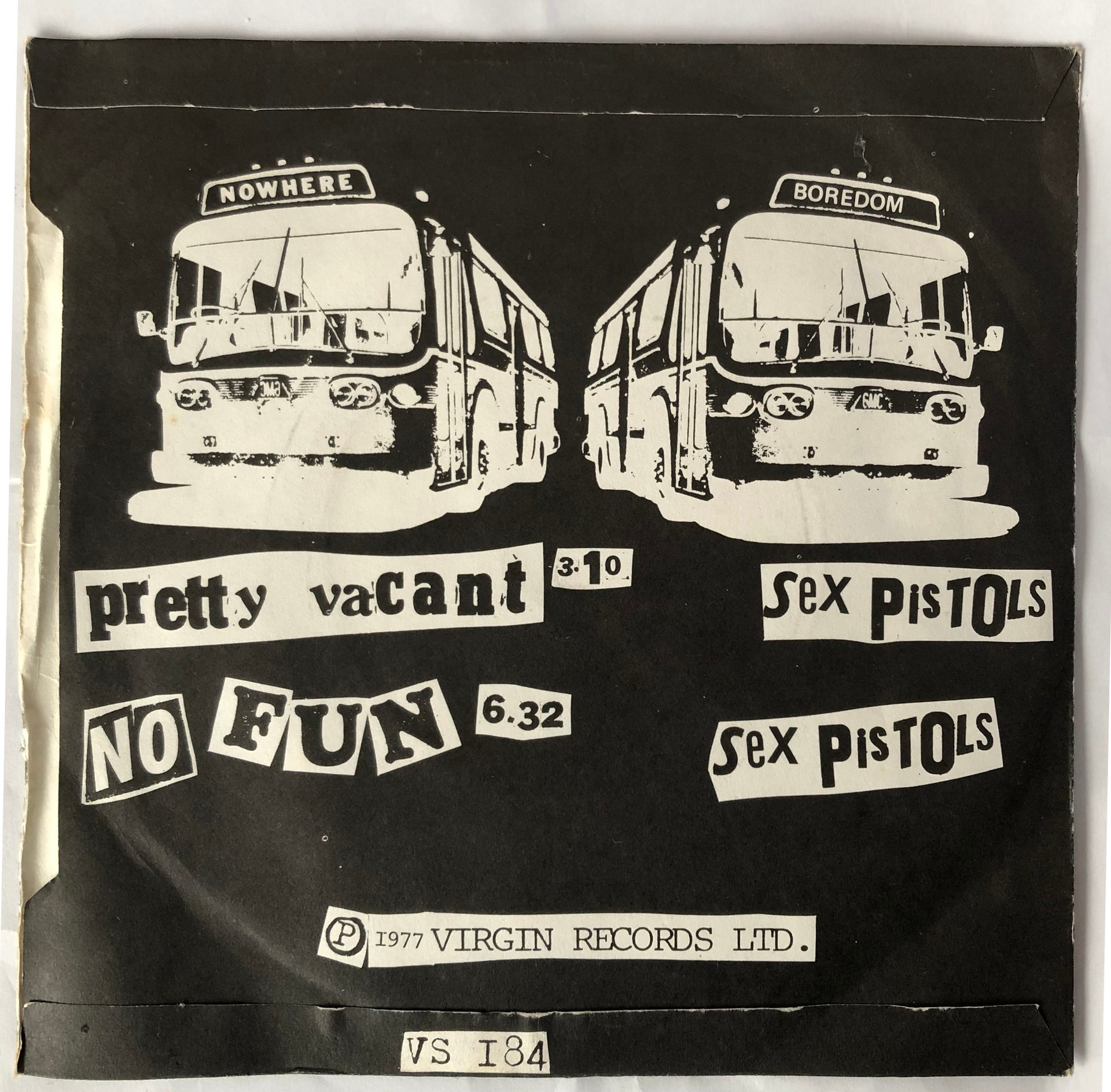

It’s a real challenge to find one piece of creative design that has remained influential from my youth right through to my later years. Record sleeve art was in many ways my first exposure to creative design. The arrival of the ‘do-it-yourself’ punk ethos empowered would-be designers like myself to start producing graphic art.

I’ve been asked many times about the influence of the Apple Mac on my work and I usually respond by saying that the Xerox photocopier was far more influential than any computer. The photocopier at my local library became a cheap substitute for the expensive and inaccessible photo mechanical transfer machine (PMT). It enabled me to produce multiple copies of an image. When Xerox machines became more sophisticated, you could even enlarge and blow things up beyond recognition. The copies allowed me to begin a practice that would remain with me for the rest of my life - cut and paste.

I’d studied art history and was familiar with Dadaism and how mixed media collage lent itself to protest and satire. As soon as Punk broke, it was easy to see how everyday objects such as the safety pin could be reappropriated and pierced through the nose of a Queen Elizabeth II portrait. Like the music, Punk inspired not only potential musicians to do-it-themselves but also potential artists as well. All you really needed was access to a photocopier and something to say, and suddenly you could produce a fanzine, a flyer and a piece of graphic art.

There are many inspirational pieces of collage that I could have chosen as an example. This work by Jamie Reid embodies not only the visual power of protest but it also challenged the established means of production.

On a May morning in London in 1977, Jamie Reid was told by Malcom McLaren, the Sex Pistols’ manager, he’d have to deliver the artwork in the afternoon at the Virgin offices. “Just on the corner of Portobello Road where Virgin had their offices there is a little art shop and in the window by chance, there was a small gold picture frame,” explains Reid. “I smashed it as I was walking down Portobello Road, got the logo and the lettering from the 100 club poster which I had in my bag with me and put them in the frame, ten minutes later I delivered it to the Art Department.”

What struck me about this particular piece was its sense of rawness and urgency. There was no band on the cover, it looked anti-promotional but most of all, it seemed to be screaming out to me saying, “you could do this”.

David Standley, Head of Creative and Content

Jamie Reid, Pretty Vacant

My creative side during my younger years was very much performance based, and when looking back at my fondest memories and who inspired me to avidly listen to music, learn lyrics, dance and perform firstly, from the comfort of my home or my best friend’s back garden, the Spice Girls were certainly in that spotlight.

The Spice Girls were all about female empowerment, expressing who you really are, entertainment and - in mine and millions of other girls’ opinions - extremely catchy tunes.

These five radical young women, known as Sporty, Baby, Posh, Scary and Ginger Spice, each had very different attributes to one another, and therefore collectively they had at least some relatability for probably the vast majority of girls in the world.

The Spice Girls became global icons, made clear by not only the amount of CDs and concert tickets they sold, but also the hundreds of other forms of media they appeared in which appealed to so many young people like me, such as photos, stickers, badges, barbie dolls and posters (to mention but a few) - their faces certainly filled up a huge amount of wall space in my childhood bedroom!

Aimee Gallagher, CBT Testing Lead, UK

The Spice Girls

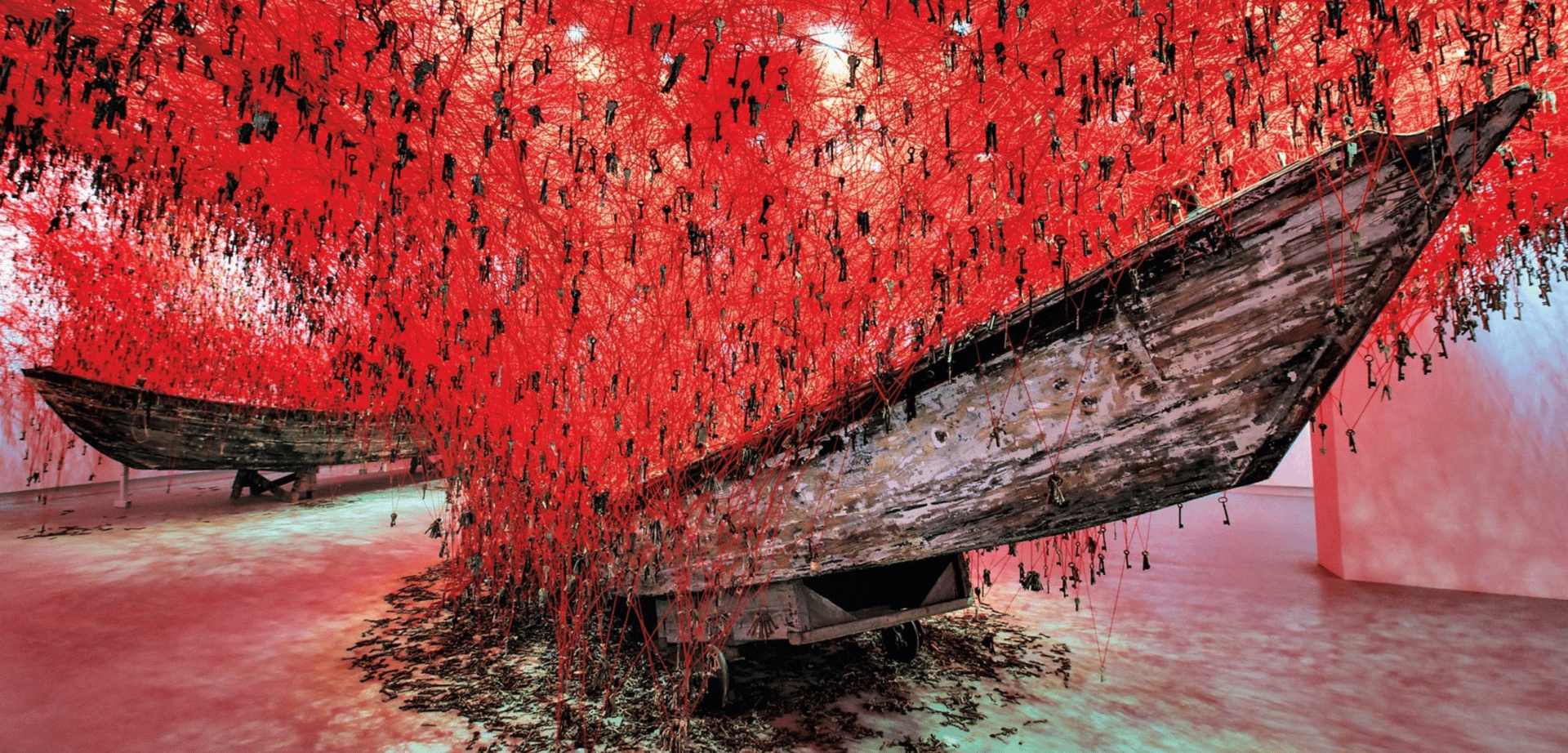

The work of Japanese installation artist Shiota Chiharu has been an inspiration since I first visited her exhibition, ’The Soul Trembles’ in the Mori Art Gallery. Chiharu’s exhibits are, in the original sense of the word, ‘awesome’. There is an immediate, almost visceral reaction, as soon as you step foot in the room. These are vast spaces, almost cavernous, with countless threads winding their way through the almost frozen air.

Shiota has become famous for her use of the thread motif, which she uses to make tangible all of the invisible forces that surround us. These threads become the connection between people, an embodiment of our pasts, our presents, our fears for the future, disappearing into a mass that makes it difficult to identify any individual.

Visiting the ‘The Soul Trembles’, I felt that, for the first time, my own personal view of the world had been laid out in front of me. In my own work, I’ve often been interested in how the connections we forge as people affect us, and how they shape our experiences of the world, so to see an artist make real something that I’d felt, and been invested in, for such a long time was an almost breathtaking experience, and one that has driven how I look at new projects.

Jack Simpson, Copywriter and Linguistic Editor

Shiota Chiharu

I’ve always been inspired by classic animation, classic Hollywood movies and American TV series.

My eye is always drawn to colour and shape: drawings or patterns found in books, nature photography, TV commercials (especially the Italian ones), and advertising. I love the colourful illustrations found in children's books and paintings like these pop portraits illustrations. These vivid colours can also be found in the natural world too, which is always inspiring.

If I think about the peak of creativity in music: Freddy Mercury and Elvis Presley had moves and rhythm that are so incredibly natural and creative.

Creativity is all around us, whether it comes from nature or people.

Colour

Maryina Vizzini, Designer

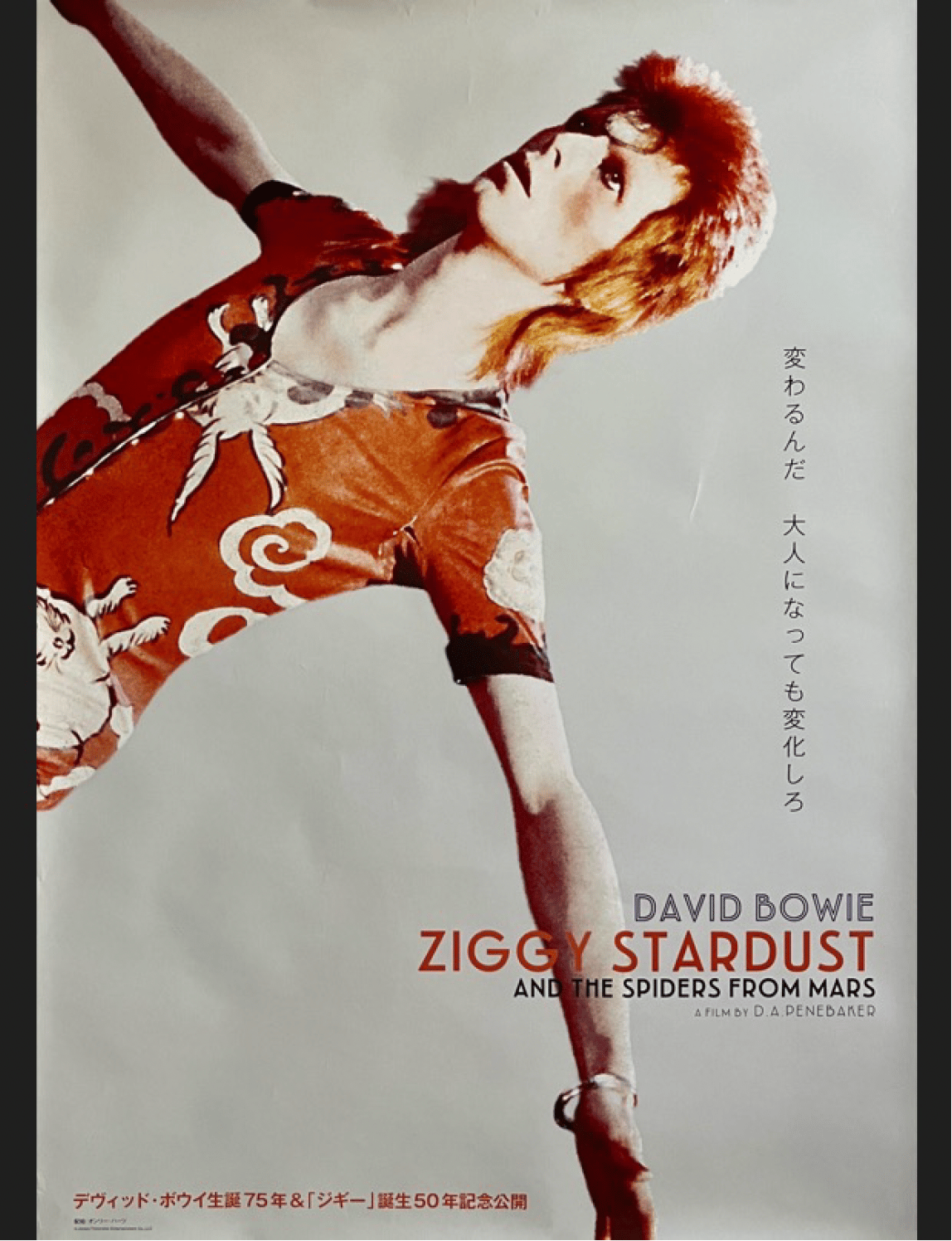

Ziggy Stardust is a character, a song, a film, an outfit, many outfits, a makeup style, a hairstyle, a creature from outer space, a singer, a musician, a rock ‘n roll superhero.

Ziggy Stardust is a persona, an alter ego, an energy, a vibe, an art form, an ideology.

Ziggy Stardust is a he, and a she, kind of both -- it doesn’t matter what Ziggy Stardust is.

Ziggy Stardust is beautiful. Ziggy Stardust is ugly. Ziggy Stardust is stupid.

Ziggy Stardust is wonderful (sings “Gimme your hands, cos you’re won-der-ful”).

Ziggy Stardust is everything.

Ziggy Starsdust (David Bowies)

Amelia Morrey, Lead Copywriter

Many people would raise their eyebrows at the idea of Barbie being inspirational media. But if we look at it as we did when we were children, if we put our egos aside and refuse to make snap judgements about what a plastic doll has to say in today’s world, we can better understand the message of this brand in a very simple way – a girl can be all she wants.

Barbie’s message about feminism is different to a lot of other media in the sense that it encourages women to dream big without losing their femininity. Traditionally, successful women only gain the respect of their male counterparts if they behave like men - if they are dressed in conservative, traditional clothing and ignore their femininity. However, Barbie explores the idea of how to be a successful woman – a pilot, an astronaut, an elite athlete or a businesswoman – while celebrating traditionally female features. In recent years the brand has extended this message to make sure all communities are represented, (even men!), and they are equally valuable.

Perhaps the main takeaway from Barbie’s storytelling is that if we taught young girls that to be successful they don’t need to ignore their identity, whatever that is, we would pave their way into highly fulfilling careers and more balanced lives.

Barbie

Sonia Arroyo, Account and Project Manager

03

THE CREATIVE MEDIA THAT INSPIRED US

THE ALPHA CREATIVE TEAM

AI generated image and prompt

In an article for the Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, Kenneth M. Heilman examined potential explanations for how non-conscious thinking can produce these moments of creative inspiration, citing possible links between lower levels of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine (caused by a relaxed state of mind) and improved creativity-boosting cognitive flexibility. While further research into the specific relationship between creative output and brain function is required, investigations into the performance of students with high levels of norepinephrine, caused by anxiety, on test questions requiring creative reasoning skills have shown that they typically performed worse than their less anxious peers with lower levels of norepinephrine. This performance gap is then closed by administration of the drug propranolol, which blocks the influence of norepinephrine (Heilman, 2016).

Studies such as these point to clear links between lower levels of stress and anxiety-induced norepinephrine and increased levels of creative output. It could be possible then, that these ‘relaxed’ states are the times that nonconscious creative thought is able to occur most freely, resulting in the ‘ah-ha’ moment when these concepts are recognized by the conscious activity of the prefrontal cortex.

New horizons for creativity

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of creativity for many is that, almost by definition, it is entirely unpredictable. As humanity continues to produce new technology and new media, the potential for its creative output is only set to expand. Consider the ways in which film has grown over the years, and think of that growth reflected in the advance of virtual reality technology or artificial intelligence.

At Rutgers’ Art & AI Lab, Marian Mazzone (Department of Art & Architectural History, College of Charleston) and Ahmed Elgammal (Department of Computer Science, Rutgers University) created an artificial intelligence known as AICAN. Using a ‘creative adversarial network’ (CAN), the software is able to produce art almost autonomously. The pair provided the algorithm with 80,000 images covering 500 years of Western art, which the system uses as a base upon which to innovate and produce new artistic works, in a process similar to the ways in which artists use previous works to inform new pieces. When the art was displayed alongside work from contemporary art fair Art Basel, the human audience was largely unable to discern which pieces were human-produced and which where machine-made. In fact, people attributed machine-generated images to human artists 75% of the time, even using words such as ‘inspiring’ and ‘communicative’ at the same levels as they did for human-produced works, suggesting that the AI had just as much creativity as its human counterparts.

As advancements in the field of artificial intelligence such as this continue to redefine what computers can do and blur the lines between human and computer output, it’s possible that we will have to redefine what it means to be creative all over again. While the Greeks believed that creativity was solely divine in its origins, and Kant sought to limit the groups of people deemed creative, future developments will spring further philosophical questions: it is only relatively recently that we’ve accepted the idea that humans are innately creative – will we extend this belief to AI?

“Creative thought is typically born out of a combination of four thought mechanisms – specifically from interactions between two modes of thought (deliberate and spontaneous), and two types of information (emotional and cognitive)”

Creativity spreads through society

As time moved on, views on humanity’s relationship with creativity changed in fits and spurts. The idea that creativity was a trait held solely by the gods gave way to the concept of divine inspiration. Though similar to the concepts put forth by Plato, later understandings of divine inspiration were more in line with Aristotle’s beliefs, giving the artist more credit for the work they produced. Crucially, the range of people believed to be creative expanded, and the conversation about who was creative moved forward to include painters, sculptors, and potentially scientists.

This was particularly notable in the creative hubs overseen by the Medici family during the Renaissance, which saw people from diverse fields come together to form communities with one goal in mind: to create something new. This gathering of talent in an attempt to promote creativity has even been mimicked in the modern era by companies such as Apple, who look to produce new technologies to appeal to the masses through these creative hubs.

During the Enlightenment, society moved further away from the heavily religious doctrine that had dominated European culture for over a thousand years, and philosophers and intellectuals began to embrace the ideals of reason and logic. As a result, many began emphasizing the concept of individual creativity over the classical belief in divine inspiration. Definitions of this ‘individual creativity’ indicated that this was an innately human trait, and one that ‘geniuses’ could use to realize artistic achievements or scientific breakthroughs.

Not all philosophers were happy to include the sciences in the creative realm. For famed 18th Century philosopher Immanuel Kant, scientists didn’t ‘create’ anything – instead, they ‘discovered’ it. Kant argued that, while artists created new rules and modes of expression through their art, scientists merely uncovered rules that already existed, whether we were cognizant of them or not. This is in stark contrast to modern conceptions of creativity, which include the idea of finding links between seemingly disparate pieces of information. This is what has led us to thinking of leading scientists such as Einstein as ‘creative geniuses’.

Modern explorations of creativity in neuroscience

Our modern understanding of creativity has become increasingly democratized. While some people are generally thought to be more creative than others, we now tend to believe that the potential to be creative lies within us all. From online self-help gurus preaching the virtues of ‘getting in touch with our creative sides’ to businesses pushing employees to think of ‘creative solutions’ to potentially mundane problems, creativity is within everyone’s reach.

In light of this modern belief that creativity is an intrinsically human virtue, study of the concept has shifted. While pre-modern examinations of creativity focused heavily on tracing its philosophical roots, modern analysis has begun focusing more on the physical neurological processes that drive ‘creative thinking’. In a paper for Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, titled The cognitive neuroscience of creativity, Arne Dietrich, professor of cognitive neuroscience, examines and outlines a ‘framework of creativity based on functional neuroanatomy’ (Dietrich, 2004).

As part of his research, Dietrich identifies that creative thought is typically born out of a combination of four thought mechanisms – specifically from interactions between two modes of thought (deliberate and spontaneous), and two types of information (emotional and cognitive) – and is then ultimately realized by the prefrontal cortex (Dietrich, 2004).

Acknowledging creativity as the ‘epitome of cognitive flexibility’, Dietrich argues that the advanced mental constructs made possible via the prefrontal cortex (such as self-reflective consciousness and willed action) are the keys to creative thinking in humans (Dietrich, 2004).

The role that the prefrontal cortex plays in the birth of creative concepts could potentially differ based on which mode of thought originally produced it. While the deliberate thought mode is instigated by the prefrontal cortex and thus produces results that seem more rational, ‘eureka’ moments in which creative ideas ‘suddenly appear’ could be identified as a result of the spontaneous thought mode.

It all started with a bang. Or perhaps it was a command: “Let there be light”. Some have said it all began in the tumultuous waters of the Nu, while others claim it all started with the founding of Takamagahara and the creation of the Earth below. Whatever the origin of our world, humanity has now existed on planet Earth for an estimated 200,000 years, and spent many thousands of those searching for answers to questions about its existence and the beginnings of the universe.

While the Big Bang is the theory favoured by modern science, humanity’s ancient civilizations created stories full of gods and goddesses to explain the origins of their world. These creation myths helped early civilizations to understand their environments: the raging seas, the violent storms and the bountiful harvests; these were the stories that shaped early concepts of ‘creativity’.

Although ‘creativity’ might appear to be a relatively simple idea to define – perhaps as the ‘ability to create something both novel and situationally appropriate’ – it’s a concept that has shifted and evolved over the centuries. In truth, the story of creativity is the story of human evolution itself.

Creation is divine

Ancient Greece is considered a civilization brimming with artistic, technical and philosophical achievement. It’s easy to see why – the core tenets of dēmokratía lay the foundation for modern democracy, Ancient Greek pottery lines the walls of museums and galleries worldwide and Homer’s Odyssey has guided the storytelling traditions of the entire European continent for millennia. Despite this, many philosophers of the time doubted the human potential to be truly creative.

As with many pre-Enlightenment civilizations, many Ancient Greeks viewed the creative process as the origination of items or ideas ex nihilo (from nothingness) – a skill generally considered to be well beyond human potential. This belief ultimately led to creativity being regarded as a divine attribute inaccessible to mortal artists. Plato himself once went on to say that artists didn’t so much make new things (create) as produce imitations of the natural world.

The people considered most in tune with ‘the creative’ were the poets. An integral part of Greek society, poetry was used in politics, philosophy and entertainment. Poets would regale audiences with stories of gods and monsters, heroes on quests to reunite with their loved ones and dramatized histories of Greek civilization. As major players in Greek life, the poets were held in high regard, and were considered to hold more authorship over their works than other artists – the modern English word poet even traces its etymological roots back to the Ancient Greek word poiein, meaning ‘to make’.

But even the poets were not immune to Plato’s denial of human creativity – rather than originating from the poets themselves, their creations were the result of divine inspiration from the muses, the poets being mere vessels. In Ancient Greek culture, the muses were inspirational goddesses regarded as the source of all knowledge contained in the poetic and lyrical arts that had been passed down through the years.

While the exact number of muses has been hotly debated in Greek studies, it is now widely believed that there were a total of nine Olympian muses, with each one associated with a specific field of the arts.

Not everyone in Ancient Greece was quite as eager to strip artists of their creative instincts – Plato’s own student, Aristotle, moved away from his teacher’s beliefs, insisting that the poets were responsible for their own creations (Niu and Sternberg, 2007). But the truth remained that creativity was not a trait accessible to all, and was strictly limited to the poets.

The story of humanity’s relationship with the creative

In the beginning

04

SEARCHING FOR A SPARK

JACK SIMPSON

Being creative means having the confidence to produce something that attracts people’s attention, and makes them wonder where the idea came from. It is an instinct that gives shapes to the most nebulous, imaginative ideas. There is a difference between being creative and creating something creative which can also come from experience, training, study, observation, imitation through curiosity about everything that surrounds us.

Martina Vizzini, Designer and Animator

From a human stand-point, I see creativity as something that begins like a spark in the mind, which then triggers a mental or physical response in a person. This response is then expressed through forming, moving, moulding, extending, or completely changing things, concepts, thoughts or voices. Put in a slightly different way - creativity starts with an inner vision, often inspired by one of the main human senses, and is then transferred to create, and make a new or slightly different impression on the person’s surroundings.

Aimee Gallagher, CBT Testing Lead, UK

People have always wondered ‘what if?’. It’s a question that has pushed human evolution for millenia, and it is the question that lies at the heart of all human attempts to be creative. We look at the world around us, and we ask ourselves: ‘what if?’. ‘What if there was a reason that the apple fell from the tree?’, ‘what if we brought daily life into our art?’, ‘what if we tried to reach the moon?’. The human mind is on an endless quest for knowledge, and while it all starts with a question, creativity is perhaps also best defined as our mission to produce an answer.

Jack Simpson, Copywriter and Linguistic Content Editor

Creativity is the mind taking flight. Seeing, hearing, feeling, touching, tasting, smelling, and engaging with the world, turning it upside down, inside out, every which way, to make sense, or nonsense out of it. Throwing it away (the world, your idea, your creative endeavour) then starting again is part of creativity.

Making connections that never existed before. Inventing, changing, breaking and mending are all thoughts, desires and acts of creating; they are the machinery of creativity. Destroy and rebuild, make it better next time, make it worse, just make it different than before.

Creativity is… “This, here, this is new”.

Amelia Morrey, Lead Copywriter

For me, creativity means crafting a new tool that did not exist before in order to resolve a problem. This problem can be something very practical, such as when our ancestors created tools to hunt animals, or it can be something conceptual, as in tools to solve philosophical questions. As an intellectual or philosophical example, thousands of years ago humans started to wonder about the coming and going of the seasons, and they came up with deities and narratives to explain the cycles of life. They created gods to validate their ideas to explain life. Gods were the tools.

In the 16th century, society started to question the place of religion as the centre of everything, this is known as the Renaissance. They created the tools (such as art) that supported this idea. In this example, they did not create hunting tools, they created art.

In today’s society, for example, the questions might be around diversity and the structure of the traditional family system – who should be our role models today? What does the perfect person look and act like? The stories that people tell nowadays to explain these things are the tools that we crafted through creativity.

In all examples, creativity is the same. It is a tool that we use to solve an issue, whether this is in the physical or the conceptual world.

Sonia Arroyo, Account and Project Manager

Simplistically, creativity is leveraging your imagination to invent something [new]. Definitions become contentious as soon as originality is brought into the equation. As originality is often used to measure creativity, I would cite the words of film director, Jim Jarmusch when he explained the creative process:

“Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination. Devour old films, new films, music, books, paintings, photographs, poems, dreams, random conversations, architecture, bridges, street signs, trees, clouds, bodies of water, light and shadows. Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic. Authenticity is invaluable; originality is non-existent. And don’t bother concealing your thievery - celebrate it if you feel like it. In any case, always remember what Jean-Luc Godard said: “It’s not where you take things from - it’s where you take them to."

David Standley, Head of Creative and Content

DEFINING 'CREATIVE':

OUR THOUGHTS ON CREATIVITY

THE ALPHA CREATIVE TEAM

05

For brands looking to improve customer satisfaction and customer loyalty through personalization efforts, these are interesting lessons. By giving consumers more direct, individual control over the user interface, there are clear improvements to both loyalty and satisfaction. However, contrary to the belief that efforts to increasingly personalize content will lead to similar results, it might be better to ensure that brands develop deep understandings of their customer bases at a segmented level (one-to-N level). With a lower investment need than one-to-one personalization, segmented personalization, when based on local expertise, can provide equal results.

The potential of ‘small data’, and interface customization

The thought of segmented content performing just as well as fully personalized content might seem odd in a consumer climate that expects brands to cater fully to their consumers’ desires. However, by focusing on quality data, and the creative presentation of carefully curated content, companies can realize impressive results.

With increased data regulations making data security and usage more difficult for companies, it will often be better for them to pivot towards ‘small data’. This would signal a shift away from the quantitative goals of ‘big data’, towards the acquisition of more targeted, quality data fields. Marry this data with deep knowledge of target locales (specific regions of a country tied together by a shared culture), and there is great potential for content to feel fully personalized, even though it is only produced at a one-to-N, or segmented, level.

The importance of understanding locale is even greater for multinational brands, which need to develop understandings of the socio-political backgrounds of their target markets, as well as their cultural values, how their citizens construct their self-image, and current consumer trends. This knowledge can then be used to either adapt content for new locales, or, as often proves more effective, create entirely new content that appeals specifically to each market.

By using carefully selected, quality customer data, and placing it in the local cultural contexts, brands are able to create segment-level content that results in emotionally resonant campaigns. As companies continue to adopt digital experiences and take a more omnichannel approach to consumer engagement, enabling user-driven interface customization can help creative, segment-level content reach the people with a specific interest in it. This is a potentially major step in furthering the perception that the brand is offering completely personalized services, helping to drive customer satisfaction and improving repeat purchase intention and business performance.

Who personalizes? And how far should they go?

In their research, Kwon and Kim identified heated discourse regarding the terms personalization and customization. Some researchers identify these as two distinct processes: personalization occurs when the corporation decides the suitable content for a customer, while customization is when the customer themselves takes the leading role in selecting the content elements they want to interact with. Others believe that personalization is ‘a process that changes the functionality, interface, information access, content and distinctiveness of a system in order to increase its personal relevance’ (Kwon and Kim, 2012). For them, customization is just one tool that companies can employ to improve personalization efforts.

In following the view that customization is a means through which companies can personalize their content, Kwon and Kim identified three degrees of personalization: one-to-all, one-to-N, and one-to-one. Put simply, these can be identified as no personalization, segmented personalization, and fully individualized personalization.

An examination of pre-existing literature on the field of personalization allowed Kwon and Kim to design hypotheses in line with common sense thinking – namely, that one-to-one content is more effective than one-to-N content, which in turn drives stronger engagement than one-to-all content. As Tyrväinen, Karjaluoto and Sarrijärvi identified in their report, personalization enables businesses to more accurately meet consumer needs, and improve customer loyalty. By increasing the customer’s feeling of control, they are able to claim ownership of the consumer experience, potentially improving their investment in the brand’s offering.

While research into how much brands should personalize their customer experiences is still relatively light, Kwon and Kim oversaw one study involving over 400 participants, which produced interesting, and somewhat surprising, results.

The study saw the researchers divide personalization strategies into two distinct groups, interface personalization and content personalization, then measure participants’ responses. In regards to interface personalization, findings overwhelmingly supported the pair’s hypothesis that one-to-one personalization led to the strongest results, while one-to-all personalization fared the worst. Interestingly however, one-to-one content personalization didn’t lead to significant improvements over one-to-N content.

These findings have been supported by research from McKinsey & Company, which has shown that 71% of consumers expect personalization, and an astounding 76% feel frustrated when they don’t experience it. In fact, consumer views on personalization perform similarly across a number of fields: 76% stated a higher likelihood of purchasing from brands offering personalized services, with 78% more likely to repurchase and recommend a brand to their family and friends. Personalized services lead to strong results for businesses, with fast-growing companies driving 40% more revenue from personalization strategies than their competitors (Arora et al., 2021).

However, in spite of the positive influence of personalized services on business performance, there are a number of challenges on the horizon leading many companies to feel apprehensive about adopting further personalization tactics.

Currently, personalization is driven largely by the acquisition of big data, which the business gathers during consumer engagement. While consumers are willing to part with their personal information in exchange for increased value or more efficient services, they are increasingly aware that their data is valuable, and thus expect businesses to keep it secure. This consumer awareness of data value, paired with increased demands for privacy and security, has meant tech giants are now looking at ways to improve user confidence and trust. Take Google, for example, which has stated it will be phasing out third-party cookies in its Chrome browser by 2024.

It’s not just the tech giants that are looking to improve privacy protections, with the application of consumer data also becoming increasingly regulated, as in the case of the EU. With the implementation of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), companies now have to invest significantly more resources to leverage the data they acquire, making data storage a much more costly endeavour.

Research firm Gartner has identified that 80% of marketers currently invested in personalization will have abandoned the practice by 2025 due to lack of return-on-investment and the headaches of consumer data management. Similarly, 80% of organizations aiming to acquire a 360 degree view of the customer will abandon this goal due to increasingly stringent privacy regulations by 2026.

The question is, then, how best to balance consumers’ expectation for personalization with the investment it requires on behalf of the business. In a study published in the Electronic Commerce Research and Applications journal, researchers Kwiseok Kwon and Cookhwan Kim of Seoul National University analyzed the role of personalized services in the context of customer retention, specifically looking at how far personalization practices should be taken in order to see effective returns.

0

%

feel frustrated when they don’t experience it

0

%

of consumers expect personalization

For strong customer engagement, personalize. It’s a message that has been pushed far and wide in business-to-customer (B2C) industries, and one that is starting to be picked up by business-to-business (B2B) markets as well. Of course, now that personalization is becoming more widespread, it alone isn’t going to be enough to stand out from the crowd. Enter hyperpersonalization – the best way for businesses to engage their potential client base. But is it really? How far should content be personalized, and who should be doing the personalization?

A quick recap: personalization is best defined as a process through which businesses target their offerings towards specific customers, potentially altering their services or allowing consumers a degree of control over the final product. These tactics have been used to varying degrees of success over the past few years. Well-known examples of businesses employing light personalization to appeal to customers include the British ‘Share a Coke’ campaign in 2013-2014, which saw the iconic Coca-Cola brand replace their logo with common British names, much to customers’ delight.

This is a relatively simple example of personalization, but it provides an interesting glimpse into how companies have been embracing personalization tactics for years in a bid to improve customer engagement with their brand and improve customer trust.

What impact does personalization have on the consumer experience?

With many companies looking for more ways to personalize their services, it’s important to understand exactly how personalization can affect the consumer experience. In a study for the Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, researchers Olli Tyrväinen, Heikki Karjaluoto and Hannu Saarijärvi of the Jyväskylä University School of Business and Economics and the School of Management, University of Tampere, looked at how personalization could influence customer experiences, with a particular focus on the burgeoning omnichannel retail sector.

The group identified that, thanks to progressive implementation of digital technology, brands were able to personalize their offerings by gathering data on customer purchases, allowing the formation of a purchasing profile displaying each customer’s needs and preferences. As these digital systems become more widespread, brands are able to integrate their marketing and purchasing channels, opening up the potential for increasingly personalized data-driven consumer experiences.

In an examination of the effects of personalization, the group underlined that the practice could provide benefits for both brands and consumers, as targeted products could appeal to customers, resulting in improved business performance. When surveyed, consumers with experience shopping in omnichannel retail environments indicated that “product recommendations based on previous purchases and personal preferences lead to new purchases”, and that personalized advertisements augment a customer’s experience, which in turn improves customer loyalty intentions.

06

TAKING IT PERSONALLY:

HOW BRANDS CAN INTRODUCE PERSONALIZATION STRATEGIES

JACK SIMPSON

References - 2. Emotions and Cultural Differences

Altarriba, J., Basnight, D. and Canary, T., 2003. Emotion Representation and Perception Across Cultures. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 4(1).

Bhugra, D. and McKenzie, K., 2003. Expressed emotion across cultures. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 9(5), pp.342-348.

Boiger, M. and Mesquita, B., 2012. The Construction of Emotion in Interactions, Relationships, and Cultures. Emotion Review, 4(3), pp.221-229.

Cooper, P. and Pawle, J., 2014. Measuring Emotion in Brand Communication. [online] QRI Consulting. Available at: <https://www.qriconsulting.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Measuring-Emotion-in-Comminication-ESOMAR-2005.pdf> [Accessed 12 September 2022].

Cho, I. and Jang, Y., 2017. Cultural Difference of Customer Equity Drivers on Customer Loyalty: A Cross-National Comparison between South Korea and United States. Quality Innovation Prosperity, 21(2), p.01.

George M. Zinkhan and Jae W. Hong (1991) ,"Self Concept and Advertising Effectiveness: a Conceptual Model of Congruency Conspicuousness, and Response Mode", in NA - Advances in Consumer Research Volume 18, eds. Rebecca H. Holman and Michael R. Solomon, Provo, UT : Association for Consumer Research, Pages: 348-354.

Hasan, Afzal & Khan, Muhammad & ur Rehman, Kashif & Ali, Imran & Sobia, Wajahat. (2009). Consumer’s Trust in the Brand: Can it be built through Brand Reputation, Brand Competence and Brand Predictability. International Business Research. 3. 10.5539/ibr.v3n1p43.

Heath, R., Brandt, D. and Nairn, A., 2006. Brand Relationships: Strengthened by Emotion, Weakened by Attention. Journal of Advertising Research, 46(4), pp.410-419.

Hong, J.W. and Zinkhan, G.M. (1995) “Self-concept and advertising effectiveness: The influence of congruency, conspicuousness, and response mode,” Psychology and Marketing, 12(1), pp. 53–77. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220120105.

Krishnan, N., 2022. How Universal Are Our Emotions?. [online] The New Yorker. Available at: <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/08/08/how-universal-are-our-emotions> [Accessed 12 September 2022].

Lau, G. and Lee, S., 1999. Consumers' Trust in a Brand and the Link to Brand Loyalty. Journal of Market Focused Management, 4, pp.341-370.

Lerner, J., Li, Y., Valdesolo, P. and Kassam, K., 2015. Emotion and Decision Making. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), pp.799-823.

Markus, H. and Kitayama, S., 1991. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), pp.224-253.

Masuda, T. et al. (2008) “Placing the face in context: Cultural differences in the perception of facial emotion.,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(3),

pp. 365–381. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.365.

Sinha, N., Ahuja, V. and Medury, Y., 2011. Corporate blogs and internet marketing –Using consumer knowledge and emotion as strategic variables to develop consumer engagement. Database Marketing & Customer Strategy Management, 18(3), pp.185-199.

Sotiris Lamprinidis, Federico Bianchi, Daniel Hardt, and Dirk Hovy. 2021. Universal Joy A Data Set and Results for Classifying Emotions Across Languages. In Proceedings of the Eleventh Workshop on Computational Approaches to Subjectivity, Sentiment and Social Media Analysis, pages 62–75, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Wierzbicka, A. (1986), Human Emotions: Universal or Culture-Specific?. American Anthropologist, 88: 584-594. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1986.88.3.02a00030

Yen, H., Lin, P. and Lin, R., 2014. Emotional Product Design and Perceived Brand Emotion. International Journal of Advances in Psychology, 3(2), p.59.

References - 4. Searching for a spark

Abraham, A. et al. (2012) “Creativity and the brain: Uncovering the neural signature of conceptual expansion,” Neuropsychologia, 50(8), pp. 1906–1917. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.04.015.

Dietrich, A. (2004) “The cognitive neuroscience of creativity,” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 11(6), pp. 1011–1026.

Heilman, K.M. (2016) “Possible brain mechanisms of creativity,” Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 31(4), pp. 285–296. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acw009.

Krippner, S. (2010) “Cave paintings and the human spirit: The Origin of Creativity and belief,” Time and Mind, 3(3), pp. 335–338. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2752/175169610x12754030956093.

Mazzone, M. and Elgammal, A. (2019) “Art, creativity, and the potential of artificial intelligence,” Arts, 8(1), p. 26. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8010026.

Morriss-Kay, G.M. (2010) “The evolution of human artistic creativity,” Journal of Anatomy, 216(2), pp. 158–176. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01160.x.

Niu, W. and Sternberg, R.J. (2006) “The Philosophical Roots of Western and Eastern Conceptions of Creativity,” Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 26.

Zwir, I. et al. (2021) “Evolution of genetic networks for human creativity,” Molecular Psychiatry, 27(1), pp. 354–376. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01097-y.

References - 6. Personalization of brand services

Arora, N. et al. (2021) “The value of getting personalization right - or wrong - is multiplying,” McKinsey & Company [Preprint]. McKinsey & Company. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/growth-marketing-and-sales/our-insights/the-value-of-getting-personalization-right-or-wrong-is-multiplying (Accessed: November 23, 2022).

Kwon, K. and Kim, C. (2012) “How to design personalization in a context of customer retention: Who personalizes what and to what extent?,“ Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 11(2), pp. 101–116. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2011.05.002.

Liles, D. (2009) “Workflow and asset management for retail marketing and merchandising in the era of hyper-localization and micro-messaging – an interview with Doug Liles of enterprise solutions,” Journal of Digital Asset Management, 5(2), pp. 83–89. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/dam.2008.57.

Parizo, C. (2022) Will google kill Third-party cookies?: TechTarget, Customer Experience. TechTarget. Available at: https://www.techtarget.com/searchcustomerexperience/tip/Will-Google-kill-third-party-cookies (Accessed: December 9, 2022).

Tyrväinen, O., Karjaluoto, H. and Saarijärvi, H. (2020) “Personalization and hedonic motivation in creating customer experiences and loyalty in Omnichannel Retail,” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57, p. 102233. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102233.